A Look At The Stability of White Dwarfs

(This calculation uses the tools of statistical mechanics. I would recommend Dr. Eugene Lim’s notes as I studied the subject through them but they’re currently unavailable. This paper goes over the calculation in quite a similar way and so does Prof. David Tong’s notes)

Introduction

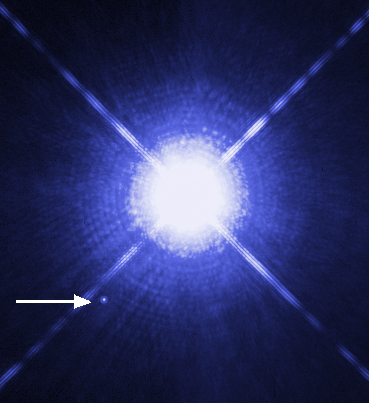

A ‘white dwarf’ is a stellar remnant left behind when stars with a mass less than $1.44 M_{\odot}$ (the Chandrasekhar limit) reach the end of their lifecycles. Their stability from collapsing in on theirselves due to the force of gravity depends on the pressure that is exerted outwards. This is called ‘electron degeneracy pressure’, which has it’s origins in quantum mechanics 1,2.

Degenerate Fermion Gas

We can begin by thinking of the two branches of elementary particles: bosons and fermions. The difference between them is that bosons have integer ‘spin’ and fermions have half-integer ‘spin’, where ‘spin’ is an intrinsic angular momentum quantum number (examples: electrons are fermions with a spin of 1/2. The photon is a boson with a spin of 1). Fermions follow a very important rule called the ‘Pauli exclusion principle’ which can be stated as follows,

“No two fermions can exhibit the same quantum numbers in a quantum system”.

For instance, if particle A has quantum numbers (1,1,1) then another particle B can’t have quantum numbers (1,1,1) because it violates Pauli exclusion. Anxything else is permitted.

Fermi - Dirac Distribution

The Fermi - Dirac distribution tells us about the average number of fermions in a particular quantum state. If we label these states as $\vec{k}$, the Fermi - Dirac distribution is:

\[\langle N_{\vec{k}}\rangle = \frac{1}{e^{\beta(E_{\vec{k}} - \mu)}+1} \tag{1}\]Here, $E_{\vec{k}}$ tells us the energy of the state $\vec{k}$, $\mu$ is called the chemical potential and $\beta = 1/K_{B}T$ where $T$ is the temperature and $K_{B}$ is Boltzmann’s constant.

The behaviour of the Fermi - Dirac distribution is quite easy to think about, at low temperatures. Lucky for us, this is the regime that we’re interested in. When the temperature is very low, the parameter $\beta$ is large. The Fermi-Dirac distribution turns into a ‘step function’ as shown below.

What this means is that the states above an energy of $\mu$ is unoccupied (by a fermion) although states below this energy are occupied. At $T = 0 K$, we will have $\mu(T) = E_{\vec{k}}$. This constant energy is called the ‘Fermi energy’ $E_{F}$.

At low energies, the fermions will have low momenta. However, recall that Pauli exclusion prevents the fermions from all crowding the lowest momentum state. If the next lowest energy state is available, it gets occupied by a fermion and so on until we reach an energy of $E_{F}$. This is whats called a degenerate fermion gas.

Energy of a Non-Relativistic Degenerate Electron Gas

We can model a white dwarf as a degenerate gas composed of electrons. Calculating the total number of electrons using the non-relativistic ‘density of states’,

\[\label{eq:nonrel} \tilde{E}(E) = \frac{8\pi\sqrt{2}V}{(2\pi\hbar)^{3}}m^{3/2}E^{1/2} \tag{3}\]The number of fermions $\langle N \rangle$ is then:

\[\begin{align} \langle N \rangle &= \int_{0}^{\infty} \tilde{E}(E) \langle N_{\vec{k}} \rangle dE \\ &= \int_{0}^{E_{F}} \tilde{E}(E) dE \\ &= \frac{16 \pi \sqrt{2}V}{3(2\pi \hbar)^{3}}m^{3/2}E_{F}^{3/2} \end{align} \tag{4} \label{eq:fermion}\]where in the second step we refer to equation \eqref{eq:step}. We also integrate up to $E_{F}$ instead of $\infty$ because there are no particles in states with energy greater than the Fermi energy. This expression can be ‘flipped’ to give:

\[E_{F} = \bigg(\frac{3 \langle N \rangle}{16 \pi \sqrt{2}V}\bigg)^{2/3}\frac{(2 \pi \hbar)^{2}}{m} \tag{5} \label{eq:fermiFlipped}\]The kinetic energy can be calculated using the density of states given in equation $\eqref{eq:fermion}$ :

\[\begin{align} \langle E \rangle &= \int_{0}^{\infty} \tilde{E}(E)E dE \\ &= \int_{0}^{E_{F}} \tilde{E}(E)E dE \\ &= \frac{3}{5}\langle N \rangle E_{F} \end{align} \tag{6} \label{eq:nonrelEnergy}\]Then, using a general expression that holds for both bosons and fermions $P = \frac{2}{3V}\langle E \rangle$, we can see that the pressure exerted by the degenerate fermion gas is

\[P = \frac{32 \pi \sqrt{2}}{15(2 \pi \hbar)^{2}}m^{3/2}E_{F}^{5/2} \tag{7}\](Remember that there is $V$ (Volume) and $\langle N \rangle$ dependence in the $E_{F}$ term) This is the fermion degeneracy pressure. The derivation thus far has assumed that $T = 0 K$ and we still have non-zero pressure arising due to the Pauli exclusion principle.

Using the fact that the gravitational potential of a spherically symmetric mass is given by:

\[E_{G} = -\frac{3}{5}\frac{GM^{2}}{R} \tag{8}\]We can approximate the mass of the star to be given by $M = \langle N \rangle m_{p}$ where $m_{p}$ is the mass of a proton. We can also use the fact that for a sphere, the volume is given by $V = \frac{4 \pi R^{3}}{3}$. Then, expressing the total energy of the star:

\[\begin{align} E_{Total} &= \langle E \rangle + E_{G} \\ &= \frac{3}{5}\bigg[ \bigg(\frac{M}{m_{p}}\bigg)^{5/3} \bigg( \frac{9}{64 \pi^{2} \sqrt{2}} \bigg)^{2/3}\bigg( \frac{(2\pi \hbar)^{2}}{m_{e}} \bigg)\frac{1}{R^{2}} - \frac{GM^{2}}{R} \bigg] \end{align} \tag{9}\]where the mass of the electron is now explicitly shown as $m_{e}$ to avoid any confusion $m_{p}$. By minimising the total energy with respect to the radius (calculating $\frac{dE_{Total}}{dR}$ and setting this equal to zero) we would notice that more massive white dwarves would be smaller. More specifically, we would find the following relation between the radius and the mass:

\[R = \frac{A}{M^{1/3}} \tag{10}\]where $A$ is a constant. This behaviour is due to the electron degeneracy pressure and seems quite counter-intuitive.

Energy of a Relativistic Degenerate Electron Gas

Since the Fermi energy corresponds to that of the last filled state, it ‘sets the scale’ for the energy of the degenerate electron gas. As the volume is compressed (when the star compactifies), this energy will increase until our non-relativistic equations break down. The density of states that was used (equation \eqref{eq:nonrel}) is based on non-relativistic physics, so we replace this with the ‘relativistic density of states’ which is:

\[\begin{align} \tilde{E}_{rel} &= \frac{8 \pi V}{(2 \pi \hbar)^{3}c^{3}}E^{2}\sqrt{1 - \frac{m^{2}c^{4}}{E^{2}}} \\ &= \frac{8 \pi V}{(2 \pi \hbar)^{3}c^{3}}\bigg( E^{2} - \frac{1}{2}m^{2}c^{4} + \cdots \bigg) \end{align} \tag{11}\]In the relativistic regime, the number of electrons is found (using the same integral as in equation \eqref{eq:nonrelEnergy} but using $\tilde{E}_{rel}$ instead of $\tilde{E}$):

\[\langle N \rangle = \frac{8 \pi V}{(2 \pi \hbar)^{3}c^{3}}\bigg( \frac{E^{3}_{F}}{3} - \frac{1}{2}m^{2}c^{4}E_{F} + \cdots \bigg) \tag{12} \label{eq:newfermion}\]The kinetic energy of the electrons can be found using

\[\begin{align} \langle E \rangle &= \int^{E_{F}}_{0} \tilde{E}_{rel}(E)EdE \\ &= \frac{8\pi V}{(2 \pi \hbar)^{3}c^{3}}\bigg( \frac{1}{4}E_{F}^{4} - \frac{1}{4}m^{2}c^{4}E_{F}^{2} + \cdots \bigg) \end{align} \tag{13}\]Looking at equation \eqref{eq:newfermion}, we can neglect all the terms except the first term in the parantheses and ‘flip’ the equation as done previously in equation \eqref{eq:fermiFlipped} to write:

\[E_{F} = \bigg[ \frac{3(2 \pi \hbar)^{3}c^{3} \langle N \rangle}{8 \pi V}\bigg]^{1/3} \tag{14}\]As in the previous case, we can find the total energy:

\[\begin{align} E_{Total} &= \langle E \rangle + E_{G} \\ &= \bigg[\frac{16}{3}\bigg( \frac{9}{64}\bigg)^{4/3} \pi^{1/3} \bigg(\frac{M}{m_{p}}\bigg)^{4/3}\hbar c -\frac{3}{5}GM^{2} \bigg] \frac{1}{R} + \mathcal{O}(R)\\ \end{align} \tag{15}\]Following what was done for the non-relativistic case, we can minimise the total energy with respect to R (by calculating $\frac{dE_{Total}}{dR}$ and setting it equal to $0$). We would find that any reference to the radius would drop out of the equation. Instead, if we calculate the second derivative and ensure it is greater than $0$ (because we’re looking for a minimum), we would find a limit on the mass of the star that ensures that the equilibrium between the gravity and electron degeneracy pressure is stable:

\[\frac{d^{2}E_{Total}}{dR^{2}} > 0 \implies M \lessapprox B \bigg( \frac{\hbar c}{G} \bigg)^{3/2}\frac{1}{m_{p}^{2}} \simeq 1.89 M_{\odot} \tag{16}\]where $B$ is a constant. This is the minimum mass that a star should have if it is to be supported by electron degeneracy pressure. This means that we wouldn’t find any white dwarfs more masssive than this.

Subramanyan Chandrasekhar first calculated this limit (more accurately, using another approach) to be $M_{Chandra} = 1.44M_{\odot}$. In our approach, we have used many assumptions (like taking $M = \langle N \rangle m_{p}$) whereas we should really take into account the ‘equation of state’.

References

-

Statistical Mechanics (Lectures notes), Eugene A. Lim (2019) ↩

-

Lectures on Statistical Physics, David Tong (2012) ↩